Saint Hildegard of Bingen: A Mystical Polymath and Channel of Ageless Wisdom

Hildegard of Bingen was a Benedictine abbess who lived in Germany from around 1098 to 1179. She's also known as Saint Hildegard and the Sibyl of the Rhine. During the High Middle Ages, she was a talented writer, composer, philosopher, mystic, visionary, and medical practitioner.

Hildegard is a significant figure in sacred monophony, and her compositions are among the most recorded in the field. Many scholars recognize her for her pioneering work establishing scientific natural history in Germany.

In this blog post, we will delve into her life and legacy, discuss the reasons behind her lasting fascination, and share some of her most profound quotes that continue to inspire and provoke thought in the contemporary world.

Who Was Hildegard of Bingen?

Hildegard of Bingen, born around 1098 to Mechtild of Merxheim-Nahet and Hildebert of Bermersheim, belonged to a family of lower nobility serving Count Meginhard of Sponheim. Traditionally considered the tenth and youngest child in her family, records suggest she had only seven older siblings. From an early age, Hildegard faced health challenges and began experiencing mystical visions, foundational elements she later detailed in her Vita.

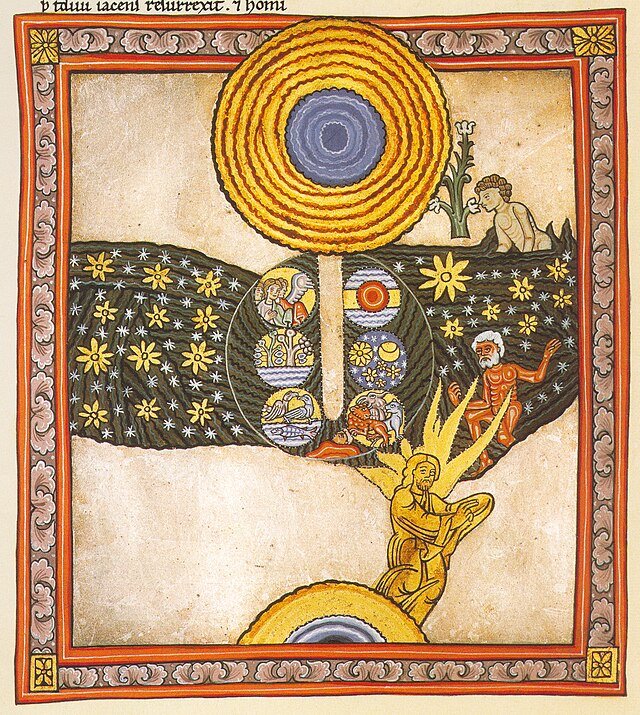

In her childhood, Hildegard's spiritual awareness was profoundly influenced by her experiences of the "umbra viventis lucis," or the reflection of the living light. She described these visions as soulful ascents to the heavens, observing distant peoples and phenomena without the mediation of her physical senses. These experiences, characterized by clarity and awakeness, accompanied her throughout life, even amidst severe illness.

Hildegard's monastic life commenced under ambiguous circumstances concerning her age and the timing of her dedication to the Benedictine monastery at Disibodenberg. It is speculated that she was offered as an oblate at the age of eight and later enclosed with Jutta of Sponheim, who was about six years her senior. By 1112, both were receiving their vows, with Hildegard under Jutta's tutelage. This period marked the beginning of Hildegard's education and her initial forays into music and liturgical studies.

Upon Jutta's death in 1136, Hildegard was elected magistra of her community, prompting her to seek a more autonomous foundation for her and her nuns. Despite initial resistance from Abbot Kuno of Disibodenberg, she successfully founded the monasteries of Rupertsberg in 1150 and Eibingen in 1165, after securing approval from Archbishop Henry I of Mainz and overcoming further obstacles through what she perceived as divine intervention.

Throughout her life, Hildegard's visions remained a central aspect of her identity and work. Initially hesitant, she was compelled by a divine command at the age of 42 to document her experiences. This led to the creation of "Scivias," among other theological and scientific writings, in which she explored the nature of her visions and their implications for understanding divine mysteries.

Hildegard's contributions were recognized within her lifetime, and she received papal endorsement for her writings. Her death on 17 September 1179 was marked by accounts of miraculous phenomena, solidifying her spiritual legacy. Posthumously, her life and works were chronicled in the Vita Sanctae Hildegardis by Theoderic of Echternach, with contributions from Godfrey of Disibodenberg and Guibert of Gembloux, ensuring her enduring impact on Christian mysticism and theology.

Visions, Music, and Writing

Visions

Hildegard von Bingen receives a divine inspiration and passes it on to her scribe.

Hildegard's spiritual journey was greatly influenced by the visionary experiences she had from the age of three until her death. Her visions were intense and immersive, and she believed them to be divine revelations that allowed her to witness the intricate connections between all of creation. Unlike mystical ecstasies that transcend consciousness, Hildegard's visions occurred while she was fully awake, a point which she emphasized in her descriptions.

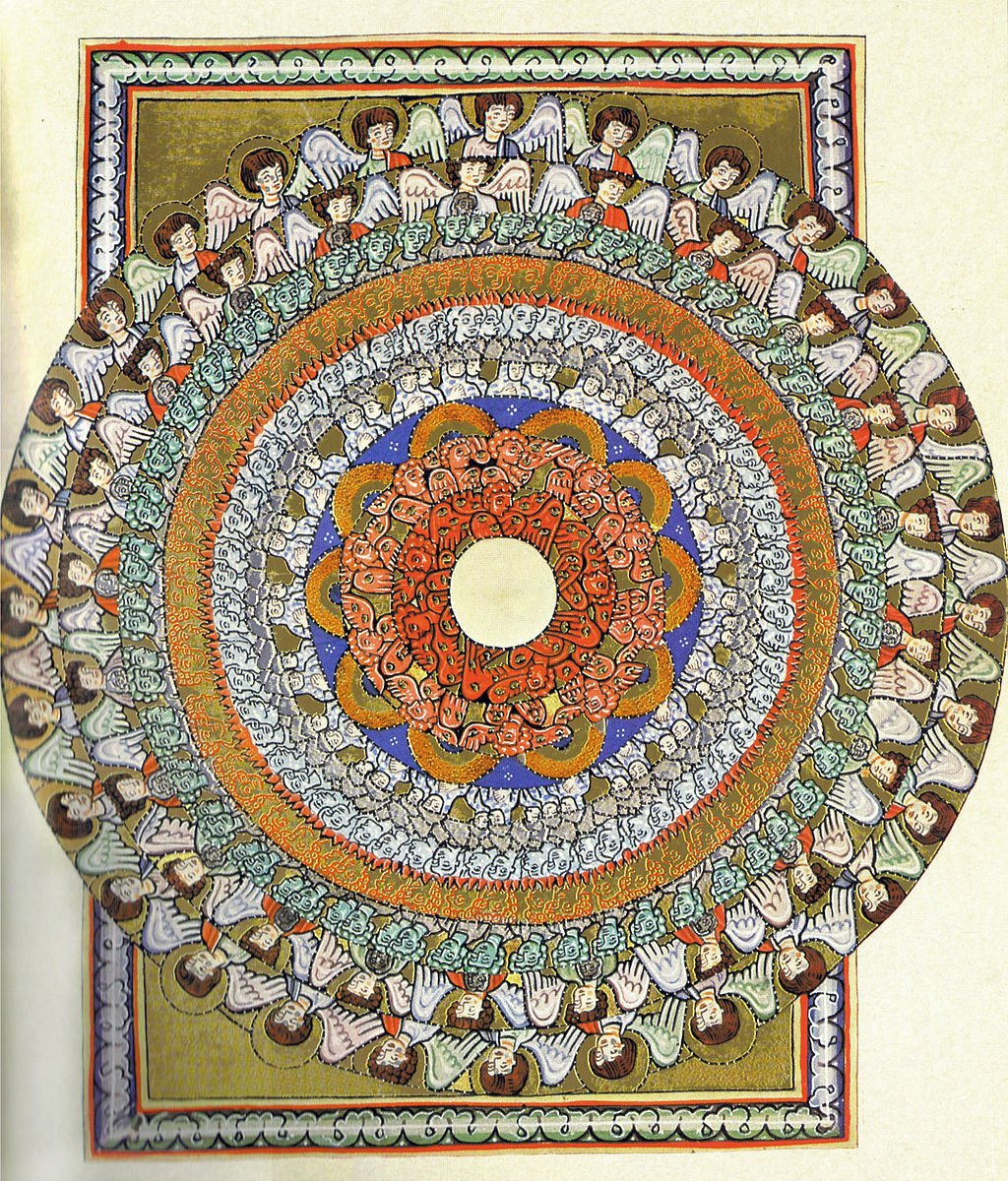

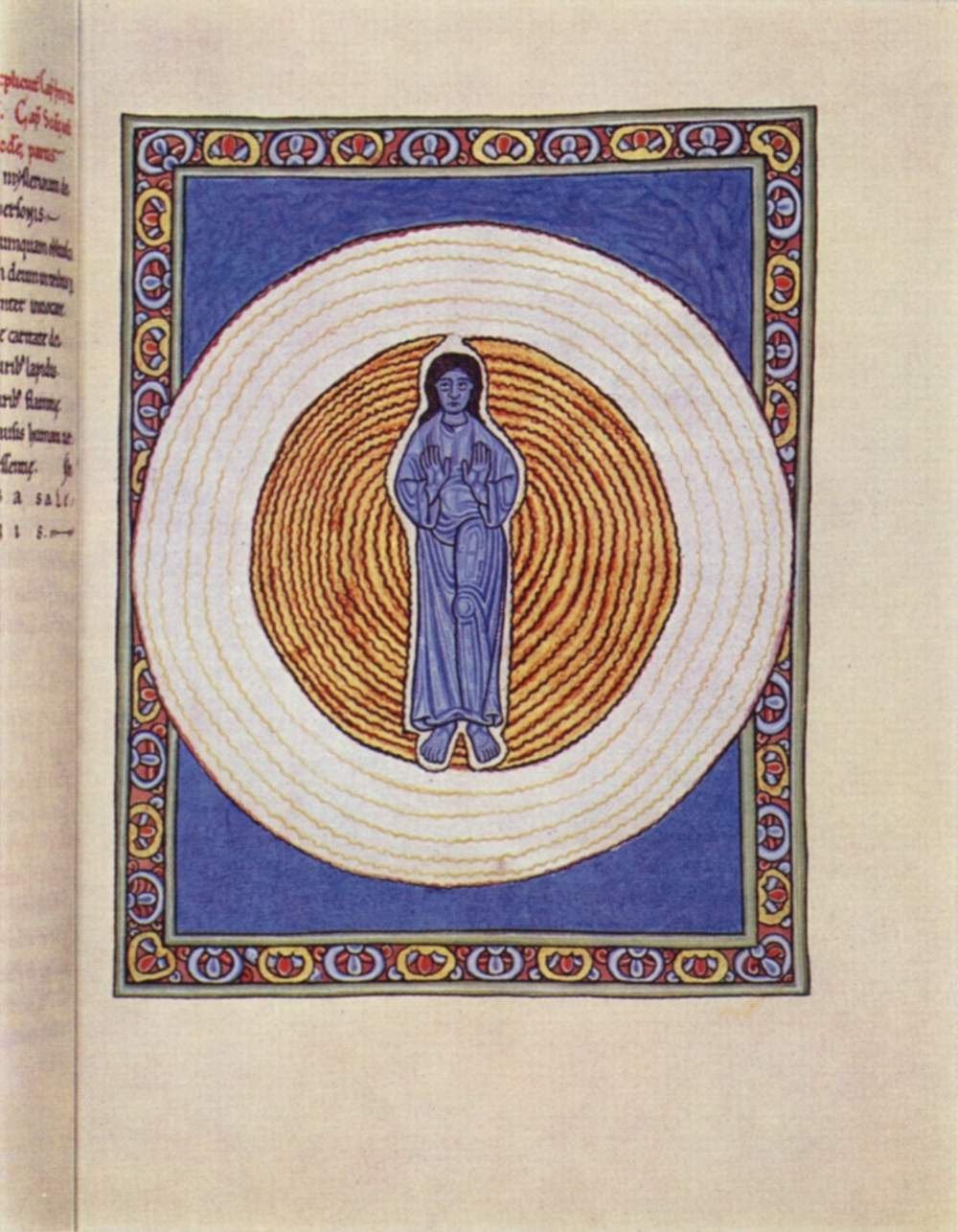

Her seminal work, "Scivias" (Know the Ways), a decade-long project completed around 1151 or 1152, presents the most detailed account of these visions. Within the book, Hildegard documents 26 visions that cover a vast thematic range, from the cosmos's genesis to eschatological reflections on the end of times, all richly accompanied by her theological insights. Hildegard viewed these visions as divine gifts meant to be shared, aiming to spiritually nurture her contemporaries and future generations.

The illustrations within the "Scivias" manuscript are crucial for fully grasping the content and essence of Hildegard's visions. Though scholars debate her exact involvement in their creation, the manuscript's frontispiece—which portrays Hildegard receiving a vision, dictating to her scribe Volmar, and making sketches—indicates her direct engagement with these visual representations. This depiction, alongside historical records, suggests Hildegard might have initiated these illustrations with sketches, which were then elaborated upon, making the visual component of "Scivias" a collaborative endeavor.

The project reached fruition shortly after Hildegard moved her convent to Rupertsberg, receiving the endorsement of Pope Eugene III, who confirmed the legitimacy of her visions and sanctioned their publication. This ecclesiastical approval not only legitimized Hildegard's experiences but also enshrined her visionary works as valuable spiritual literature.

Music

Hildegard's contributions to music are equally remarkable. She composed an extensive body of liturgical songs, including antiphons, hymns, and sequences, that were innovative for their time and remain influential in the field of sacred music.

Her compositions, characterized by their soaring melodies and expressive text settings, were designed to convey spiritual messages and enhance liturgical practices.

"Ordo Virtutum" (Play of the Virtues) is one of her most notable works. It is an allegorical morality play that predates the modern opera. It features a cast of virtues and the soul engaged in a struggle against the devil—a purely spoken role, as Hildegard believed evil could not produce divine harmony.

This work showcases her belief in the redeeming power of music and its role in the spiritual journey.

Writing

Beyond her visionary and musical works, Hildegard was a prolific writer on various topics, including theology, medicine, and natural science. Her theological writings offer deep insights into her understanding of Christian doctrine and mysticism, reflecting her contemplations on humanity's relationship with the divine.

In the realm of natural science and medicine, works like "Physica" and "Causae et Curae" reveal Hildegard's keen observation and knowledge of the natural world. She detailed the medicinal uses of plants, animals, and minerals alongside theories on the human body and disease, demonstrating an approach that was both practical and deeply interconnected with her spiritual beliefs.

Hildegard's holistic view of the world, where spirituality, science, and art converge, is evident in all her works. She saw the divine in all aspects of life and sought to communicate this vision through her writings and music. Her legacy, as preserved through her visionary texts, musical compositions, and scholarly writings, continues to inspire and influence those interested in the intersections of faith, art, and science.

Hildegard of Bingen Quotes

Hildegard's words continue to resonate, reflecting her deep spiritual insight and understanding of the human condition.

Here are some of her quotes that capture the essence of her wisdom:

“It is easier to gaze into the sun, than into the face of the mystery of God. Such is its beauty and its radiance.”—Hildegard of Bingen

“She is so bright and glorious that you cannot look at her face or her garments for the splendor with which she shines. For she is terrible with the terror of the avenging lightning, and gentle with the goodness of the bright sun; and both her terror and her gentleness are incomprehensible to humans.... But she is with everyone and in everyone, and so beautiful is her secret that no person can know the sweetness with which she sustains people, and spares them in inscrutable mercy.” ― Hildegard of Bingen

“The Word is living, being, spirit, all verdant greening, all creativity. This Word manifests itself in every creature.”

― Hildegard of Bingen

“I am the fiery life of the essence of God; I am the flame above the beauty in the fields; I shine in the waters; I burn in the sun, the moon, and the stars. And with the airy wind, I quicken all things vitally by an unseen, all-sustaining life.” ― Hildegard of Bingen

“Like billowing clouds,

Like the incessant gurgle of the brook,

The longing of the spirit can never be stilled.”

― Hildegard von Bingen

“We cannot live in a world interpreted for us by others. An interpreted world is not a hope. Part of the terror is to take back our listening, to use our own voice, to see our own light.” ― Hildegard of Bingen

“The soul is the greening life force of the flesh, for the body grows and prospers through her, just as the earth becomes fruitful when it is moistened. The soul humidifies the body so it does not dry out, just like the rain which soaks into the earth.” ― Hildegarde of Bingen

“Divinity is in its omniscience and omnipotence like a wheel, a circle, a whole, that can neither be understood, nor divided, nor begun nor ended.” — Hildegard of Bingen

“Just as a mirror, which reflects all things, is set in its own container, so too the rational soul is placed in the fragile container of the body. In this way, the body is governed in its earthly life by the soul, and the soul contemplates heavenly things through faith.” — Hildegard of Bingen

“Dare to declare who you are. It is not far from the shores of silence to the boundaries of speech. The path is not long, but the way is deep. You must not only walk there, you must be prepared to leap.” — Hildegard of Bingen

Conclusion

Hildegard of Bingen's legacy is a testament to the power of vision, intellect, and spirituality. Her life and work offer a fascinating glimpse into the mind of a woman who was not only ahead of her time but also profoundly connected to the ageless wisdom, the perennial philosophies that take root, blossom, and decay from age to age, only to be born again through various iterations and vessels.