If Plants Could Think: The Science of Plant Intelligence

The plant world is a complicated pharmacopeia. American philosophers and naturalists have long venerated the plant world for its ancient, primordial wisdom. “They do not preach learning and precepts, they preach, undeterred by particulars, the ancient law of life,” writes Herman Hesse. “I believe that there is a subtle magnetism in Nature,” Thoreau tells us, “if we unconsciously yield to it, [it] will direct us aright.” It’s not surprising that we still feel this way about nature, especially in popular culture.

Why are there trees I never walk under

But large and melodious thoughts descend upon me?

—Walt Whitman, Leaves of Grass, 1892

James Cameron’s movie, Avatar, shows off a whole world that functions like one, vast, neural network. A living mind. Navi’s balanced ecosystem is achieved through plants and animals communicating with each other. Daron Aronofsky’s The Fountain explores the pharmacological promise of the Tree of Life—hidden deep in a Central American rainforest—able to cure disease and extend life indefinitely. More infamously, M. Night Shyamalan’s The Happening explored how plants could become the focus of a horror film where—spoiler alert—plants around the world learn to release a deadly, psychoactive gas, forcing hapless people in the vicinity to kill themselves. The last example is a little bizarre, but despite its mixed public reception, Shyamalan was adapting some actual science—albeit in a very exaggerated way. More on that in a second.

There’s a goofy scene in The Happening where Mark Wahlberg’s character tries to assuage a potted tree not to kill him. “Just want to talk in a very positive manner. Giving off good vibes,” he says, “we’re just here to leave the bathroom…I hope that’s OK.”

Luckily for Wahlberg, the tree is just plastic.

Still, the idea that you should talk with your house plants is a trivial familiarity. We’ve heard it before—somewhere—that playing classical music around plants helps them grow better. Especially Mozart.

But where did all these ideas come from? What’s the actual science behind “plant intelligence?”

Can Plants Think?

These ideas struck a cord with popular consciousness way back in the 1970s, when New Age ideas were just starting to get popular. A little book called The Secret Life of Plants, by Peter Tompkins and Christopher Bird, was published 1973.

There are many interesting vignettes in the book, from actual science experiments to more metaphysical musings. As one New Yorker writer describes it, The Secret Life of Plants is a “beguiling mashup of legitimate plant science, quack experiments, and mystical nature worship.” (Incidentally, this sounds like my kind of book.)

One story of note involves Cleve Backster, a C.I.A. polygraph expert who hooked up a houseplant—a dracaena—to a galvanometer. To his utter surprise, when he visualized the plant on fire, he could make the needle rise. He followed up with a series of experiments, where, he claims, plants would also react when other species were being harmed. Boiling live shrimp in the same room, for instance, would make the needle rise. Unfortunately for Backster, other scientists were not able to repeat his findings, and The Secret Life of Plants soon became the bane of credible research. Daniel Chamovitz, an Israeli biologist, credits the book for scaring away scientists from the field. Fortunately for our question—whether plants can think—the jury is still out.

Research became fringe after that, but it didn’t stop.

Green Bites Back

In 1983, new studies were published demonstrating that Willow, Poplars, and Sugar Maples were able to warn each other about insect attacks and even slow down the metabolism of their grubby assailants. The leaves chewed on by insects would release “volatile chemical compounds” in the air, triggering the other trees to release them too. These chemicals slowed down the growth of the caterpillars. When fed leaves from undamaged willows that lived nearby, caterpillar growth would also slow down.

In another case, David Rhoades published a study showing how plants could also release chemicals that made their leaves taste unpalatable (read: gross) to insects.

Further studies demonstrated that plants could also do things like disrupt insect digestion, and even warn other plants to do the same. When damaged sagebrush leaves were put into an airtight container with tomato plants, the tomato plants began producing protein inhibitors too. Another study discovered that maize, when chomped on by beet armyworms, releases a chemical to attract a species of wasp that uses those caterpillars to lays its eggs in.

It’s not just insects, but animals too. In Peter Wohlleben’s recent book, The Hidden Life of Trees: What They Feel, How They Communicate, he describes how giraffes in the savannah have to deal with particularly witty umbrella thorn acacias. Minutes after they begin feeding, the acacia leaves start pumping toxic substances. Giraffes can sense when this is happening, so they move on to other acacias—but up to 100 yards away. The giraffes, perhaps instinctively, know that they have to reach acacias who haven’t been “warned” about them and aren’t releasing the toxins.

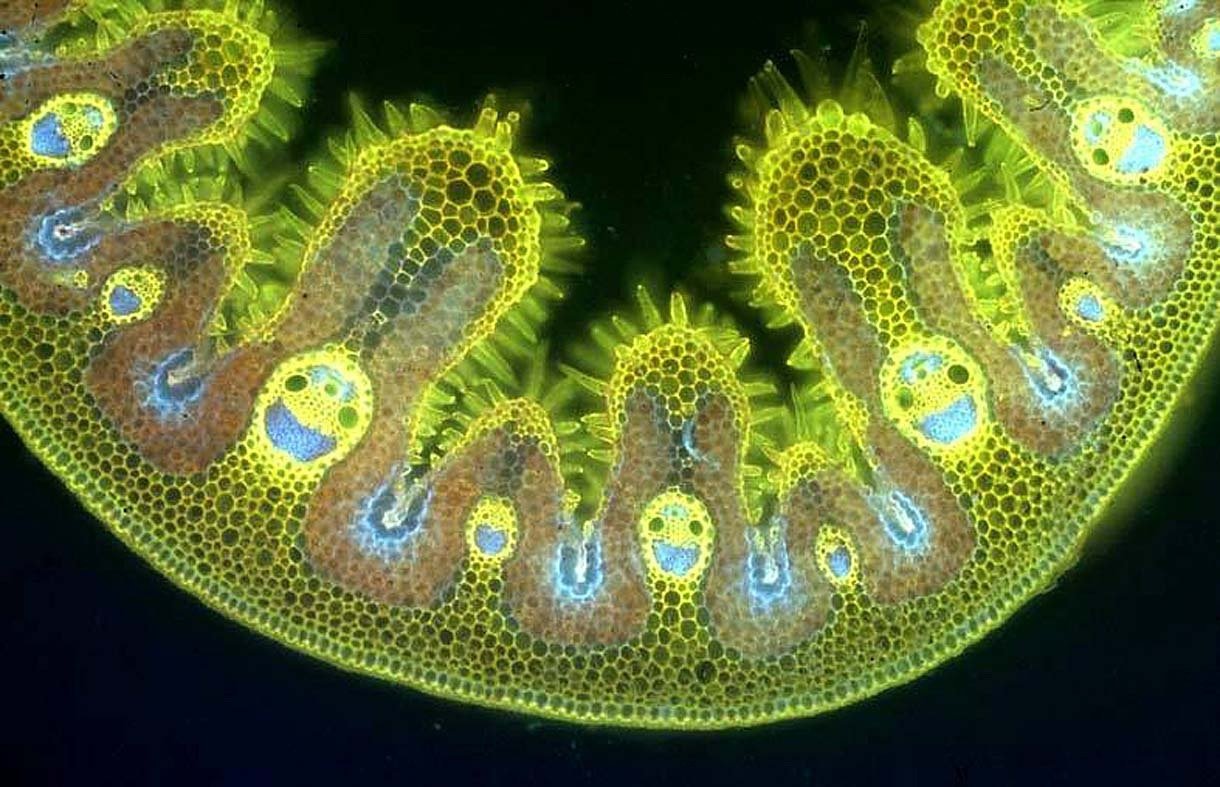

Some studies have shown that plants do, indeed, use electrical impulses—like an animal nervous system—but it travels much slower, at about a third of an inch per second. When a bug or an animal starts chewing on a leaf, the plant, in a sense, knows it’s happening. It’s just operating on a much slower timescale. This can be beneficial for plants, giving them more time to pinpoint the exact location and identity the particular species that decided to have them for lunch. Bugs, for example, produce different saliva, and a plant can “taste” (again, loose analogies here) it and respond with the proper toxin for the specific predator.

The smell of freshly cut lawn is actually a cocktail of alcohols, aldehydes, ketones and esters—all spelling out, in olfactory language—“DANGER!” The suburbs were never a friendly place, anyway.

WIRED magazine, in a recent exploration of plant intelligence, summed up these examples nicely:

“…The emerging picture is that plant-eating bugs, and the insects that feed on them, live in a world we can barely imagine, perfumed by clouds of chemicals rich in information.”

This lends itself to the widely accepted benefits of the plant world’s biochemistry. They are simply awe-inspiring producers of medicines of all types. Many basic medicines, like over-the-counter pain killers to harder drugs, like opiates, derive from plants. We can marvel and appreciate them for their “complex molecular vocabulary,” cultivated over millions of years of Earth’s deep time.

Ancestral Roots

Peter Wohlleben, while managing a forest in the Eifel mountains in Germany, discovered an ancient root system—about 400 years old—kept alive by its own descendants. Neighboring trees actually help each other, in many cases, either through sharing water and nutrients through their own roots, or passed along through the fungal networks that grow around them and serve as an “extended nervous system.”

Trees can even tell the difference between roots that belong to their relatives and other species.

Trees can also “share space” in the forest canopy. While many times a forest can look like a “shoving match” in slow motion, trees are careful to help their “friends” and not overstep their growing spaces. Meanwhile, they grow thick, reinforced areas of their branches in the direction of “non-friends.”

Trees value connection. They like to make space for their friendly neighbors and relatives, but will grow out an reinforce their crown in the direction of “non-friends.” Trees can be aggressive, for certain, but they can also be cooperative, friendly, and seek to help each other out for the sake of preserving the whole forest.

Peter Wohlleben offers a profound reflection on this view, quoted at length:

“The reasons are the same as for human communities: there are advantages to working together. A tree is not a forest. On its own, a tree cannot establish a consistent, local climate. It is at the mercy of wind and weather. But together, many trees create and ecosystem that moderates extremes of heat and cold, stores a great deal of water, and generates a great deal of humidity. And in this protected environment, trees can live to be very old. To get to this point, the community must remain intact no matter what. If every tree were looking out only for itself, then quite a few of them would never reach old age… A tree can be only as strong as the forest that surrounds it.”

The science behind plant intelligence confirms a view of life that biologists like Lynn Margulis have been advocating for decades: that the language of nature is cooperative: “The view of evolution as a chronic bloody competition among individuals,” she writes in Microcosm: Four Billion Years of Evolution from Our Microbial Ancestors, “a popular distortion of Darwin’s notion of ‘survival of the fittest,’ dissolves before a new view of continual cooperation, strong interaction, and mutual dependence among life forms.” What better place to discover this than the forests that now lie at the outskirts of our neighborhoods and at the edges of our cities. “Life did not take over the globe by combat, but by networking.” Take it from the trees: to live together in a resilient ecosystem, you’ve got to grow together. “Life forms multiplied and complexified by co-opting others, not just by killing them.”

In the collapsing political sphere, today, we humans could learn a thing or two from our plant friends.

Plant Neurobiology

In 2006, Trends in Plant Science, a journal, published a proposal for a new field: “Plant Neurobiology.” While it did receive a lot of criticisms—many scientists were, and are, still wary about using neurological metaphors for plant life—with decades of new research, the field holds great promise. It likens what plants have to think as an “information-processing system,” able to coordinate a plant’s behavior. Research has shown that plants have been discovered to produce serotonin, dopamine, and glutamate—each and all neurotransmitters. One critical scientist, Lincoln Taiz, writes that plant neurobiologists are guilty of “over-interpretation of data, teleology, anthropomorphizing, philosophizing, and wild speculations.” Further, he suggests that any future science “will be explained…without recourse to animism.” As something of a philosophical animist myself, that last part amused me. But plant neurobiology is anything but hokey. Many of the scientists in the field are well aware that plants don’t have literal brains, and aren’t claiming that, anyway. The kind of intelligence plants exhibit are more analogous to insect colonies, where brain-like behavior is an “emergent property of a great many mindless individuals organized in a network.” The study and science of networks has breathed new life in the field of plant intelligence for very clear reasons: swarm behavior, distributed networks and even flocks of birds exhibit what appears to be intelligence, even without there being literal brains present. Might the emergent intelligence of a plant, and by extension, the complex field of relationships in its local ecosystem, display similar emergent intelligence properties?

Whether it’s plant neurobiology or realizing that plants and trees are social beings—yes, beings—that have their own sense of time and even their own olfactory language and melodic, biochemical pharmacopeia, we can appreciate the vast intelligence present right outside our doorsteps. It makes the “smart” devices, despite their brilliance of craft, appear as dulled glass in comparison. The movies, like Avatar, are true, after all—we don’t need to look to the stars for the intelligence we seek. The plants outside our door, or sitting quietly on our windowsill, have already made contact. It’s we who are, only now, coming around to hearing them.

Sources

The Intelligent Plant, The New Yorker

The Secret Life of Trees, Brain Pickings

The Science of Plant Intelligence, WIRED