Gendün Chöphel: The Legendary Tibetan Free Thinker

Gendün Chöphel was a rebellious Tibetan monk who, through his controversial writing and illustration, inspired radical change in Tibetan culture. Considered to be the reincarnation of a famous Buddhist Lama, he is one of the most notorious Tibetan intellectuals of the 20th century.

Born in 1903, Chöphel was a man of many creative and intellectual pursuits. He was regarded as an artist, a poet, a writer, and a scholar who published a collection of influential works throughout his adventurous life.

Chöphel was the son of a revered monk in Rebkong, Amdo region. At a young age, the boy was sent to the monastery known as Yama Tashikyil to begin his Buddhist studies. When he turned 17, the young monk was sent to Labrang to complete his monastic education.

Labrang Monastery

The Labrang Monastery was a renowned temple in Eastern Tibet whose reputation attracted monks from all over central Asia. It housed one of the largest monastic universities of the 20th century. At the time, there were over 4000 Monks studying and living within its white walls and gilded roofs.

The art of philosophical debate was an important aspect of the monastic lifestyle with a longstanding history of over 800 years. The traditional format involved one monk presenting a philosophical question to a challenger, who then responds with an answer of increasing wit and wisdom.

This practice had been established to train the student’s critical understanding, but had deteriorated into an empty ritual where the memorization of responses made by past scholars was the only way to defeat your opponent.

Chöphel revitalized these monastic debates by making a name for himself with his unconventional approach. He always found a way to defeat his adversaries with an eccentric but effective response. This left a deep impression on the methodical monks of Labrang, who continue to tell stories of his debates to this day.

The young innovator was memorable for more than his wise words. It was well known in the monastery that he could make mechanical toys he fashioned out of broken clock parts. An elderly monk recalled that Chöphel would boast about creating a mill without needing water if he had the proper materials. His radical ideas upset the monks, creating undue resistance to his ingenuity.

Chöphel (right) with Rakra Tethong Rinpoche standing in front of the Potala Palace in Lhasa (c. 1949)

In 1934, Chöphel turned away from life at the monastery. After becoming disillusioned with the rigidity of the monastic traditions, he departed from the temple. He moved to Lhasa, supporting himself with the talent for painting he developed as a monk. Chöphel could paint extremely realistic portraits for his clients, some of which still exist today as a testament to his mastery.

Chöphel soon realized that his society shared the same stagnancy as the monastery, having closed itself off to the world's progress. His criticism of the ruling authorities grew, and he began investigating the source of the motionless monotony surrounding him.

After discovering wall murals and ancient writings that revealed the violent, war-torn history of Tibet to the young academic, his worldview was completely shattered. Until now, Chöphel had only heard Tibetan history through Buddhist legends taught by monks. This revelation ignited a fire within, which compelled him to seek out the true history of his country.

Rahul Sankrityayan

Around the same time, Chöphel became acquainted with Rahul Sankrityayan, a traveling historian and activist, on a research expedition to recover Buddhist manuscripts that no longer exist in India. After extensive deliberation, they decided to travel through Tibet together, visiting countless monasteries in search of these rare manuscripts.

Sankrityayan saw his historical journey as an aspect of his activism. To him, acquiring knowledge of the past was a way to resist the British colonial occupation effectively. Chöphel became inspired by Sankrityayan’s rebellion against the powers that be and was most likely influenced by his historical method of activism.

Chöphel and Sankrityayan traveled together for months, visiting many old monasteries throughout Tibet and eventually reaching the Sakya Monastery in 1938. At long last, they had uncovered all the missing manuscripts which had been destroyed or lost to time.

Buddhist Scriptures Wall in the main hall of Sakya Monastery

After experiencing everything Tibet had to offer, Chöphel felt drawn to the land his companion would speak so fondly of. He decided to return with Sankrityayan to India, and at the age of 32, they arrived at the Ganges River. Shortly after his return, Sankrityayan was arrested for his activism in the independence movement and was thrown into prison.

A portrait of Gendün Chöphel while in India (1936)

Chöphel never saw his companion again but eventually decided to continue on his pilgrimage through the exotic country he had only just begun to discover. His journey began with the ancient Buddhist pilgrimage sites but quickly extended to notable locations throughout the foreign land.

Chöphel’s adventure through India lasted for many years, and he wrote down everything he saw. His personal notes later became the foundation for a travel guide of India that is still used today. Through his written accounts and painted illustrations, he introduced Tibetans to unknown cultures and encouraged them to learn from new and old traditions. Some Tibetans consider this to be his greatest accomplishment.

Chöphel spent some time writing newspaper articles for the Tibet Mirror, a small Indian newspaper read in Lhasa by open-minded nobility and monks. Tibet did not have a newspaper at the time, and this was the first of its kind. He went on to write a collection of essays, translations, and historical works that expressed his critical reflections on the politics and religion of various countries, including Tibet.

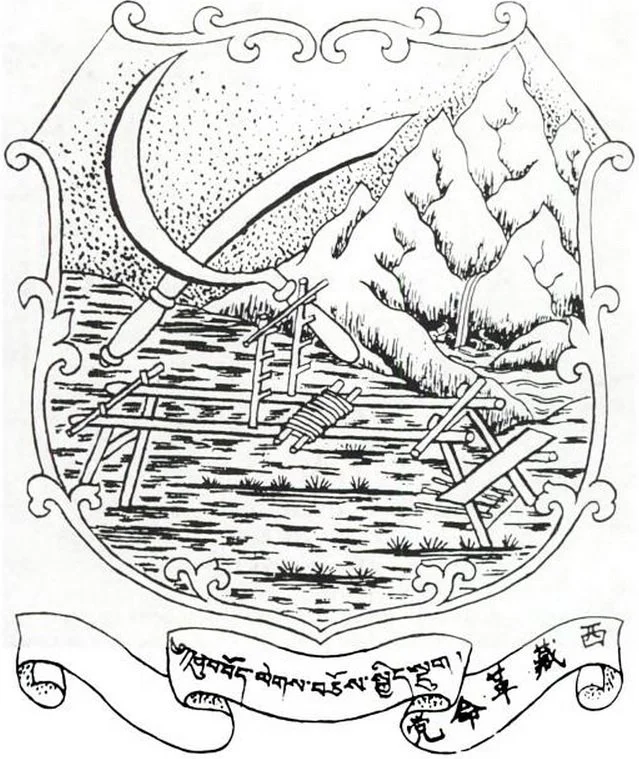

While in Kalimpong, India, Chöphel was asked to design an emblem for the Tibetan Improvement Party. He accepted and created an image that would eventually become his downfall: a crossed sword and sickle that sent the British occupation into a panic.

Insignia of the Tibet Improvement Party

After returning to Lhasa, Tibet, in 1946, Chöphel was arrested under suspicion of being a communist spy. His written and historical works were confiscated, and he was imprisoned. After three years of detention, Gendün was freed, returning to society as a depressed, broken man. After the government realized the significance of his work, they released some of his written material and demanded that he continue writing. Chöphel, having lost the will to write, refused these demands.

Gendün Chöephel’s wife, Tseten Yudron, gave an account of his remaining days:

“After his release, we lived together for two years. Not much time for us. He died shortly afterwards. If he hadn’t drunk so much he would have lived longer. He got crazier and crazier, at the end he was barely a human being.”

Despite his fall from grace, Gendün Chöphel’s life was an inspiring embodiment of revolutionary thinking. No Tibetan before him had ever written political history about Tibet, which was surely a game-changing component of the socio-political climate.

This sole individual’s actions revealed a previously unknown chapter in the culture of Tibet, and it is clear that many still proudly recognize Gendün Chöphel’s significant contributions to Tibetan history.

References

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Gend%C3%BCn_Ch%C3%B6phel